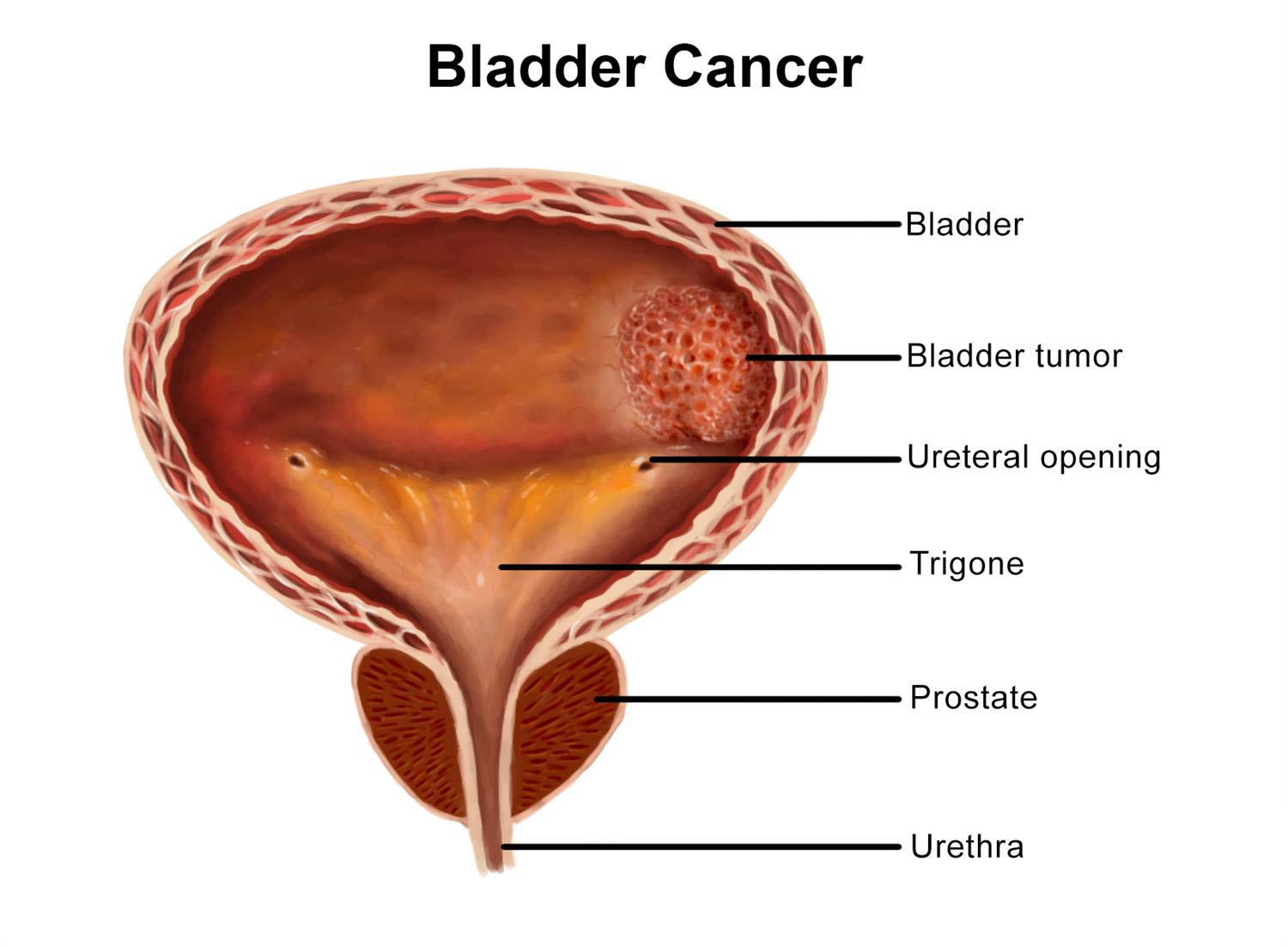

Bladder cancer is a common type of cancer that begins in the cells of the bladder. The bladder is a hollow muscular organ in your lower abdomen that stores urine.

Bladder cancer most often begins in the cells (urothelial cells) that line the inside of your bladder. Urothelial cells are also found in your kidneys and the tubes (ureters) that connect the kidneys to the bladder. Urothelial cancer can happen in the kidneys and ureters, too, but it’s much more common in the bladder.

Most bladder cancers are diagnosed at an early stage, when the cancer is highly treatable. But even early-stage bladder cancers can come back after successful treatment. For this reason, people with bladder cancer typically need follow-up tests for years after treatment to look for bladder cancer that recurs.

Blood in the urine (hematuria) is often the most common sign of bladder cancer. There are other symptoms to watch for as well. They may be caused by something other than bladder cancer, but it’s important to have them checked out by a doctor.

Signs of Bladder Cancer

Blood in the Urine

It may be very faint with a pink tinge, or the blood may be obvious. Hematuria often occurs without pain or other urinary symptoms. Blood may not be present in the urine all the time — it may come and go. If blood is not visibly noticeable, it may be detected by a urine test.

Irritation, Pain, or Burning while Urinating

Any pain while urinating could be a sign of bladder cancer.

Urgency

Bladder cancer can cause a feeling of needing to urinate immediately, even though the bladder is not full.

Frequency

The need to urinate often may be caused by bladder cancer.

Having to Urinate at Night

Bladder cancer may wake you up at night with an overwhelming need to urinate.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a common symptom of many different types of cancer, including bladder cancer.

Flank Pain

Pain between the abdomen and back on one side of the body could be a symptom of bladder cancer.

Loss of Appetite

Bladder cancer may make it uncomfortable to eat or make you feel like you don’t want to eat at all.

Weight Loss

Weight loss is a common symptom of many types of cancer, including bladder cancer.

The type of bladder cancer you have depends on the type of cell in which the cancer began. Pathologists can diagnose the type of cancer by looking at tumor cells under a microscope.

Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder

Most bladder cancers — about 90 percent — begin in the cells on the surface of the bladder’s inner lining. This type of cancer is called urothelial carcinoma (also called transitional cell carcinoma). Most urothelial carcinomas are noninvasive. That means the tumor stays within the bladder’s inner lining.

Urothelial carcinoma also has rarer subtypes, or “variants.” These differ depending on how the cells appear under a microscope. The variant of urothelial carcinoma affects the treatment. The variants are called:

- plasmacytoid

- nested

- micropapillary

- lipoid cell

- sarcomatoid

- microcystic

- lymphoepithelioma-like

- inverted papilloma-like

- clear cell

Bladder cancer can affect anyone. Major risk factors include smoking, exposure to certain chemicals, and having a family history of the disease.

Smoking

Tobacco use is the biggest risk factor for developing bladder cancer. This risk increases with the amount and length of time smoking. Cancer-causing chemicals inhaled from burning tobacco enter the bloodstream. The body filters them from the blood through the kidneys and transfers them to the bladder to be removed from the body. The chemical-containing urine can cause damage to the cells in the bladder. Avoiding smoking is the most effective way to lower the risk. People who have quit smoking have a lower risk of bladder cancer compared with active smokers. The risk continues to drop the longer one has stopped smoking.

Chemical Exposure

Frequent exposure to chemicals that are commonly used in certain jobs may increase bladder cancer risk. This includes chemicals called aromatic amines. They are most commonly used in the textile, dye, rubber, leather, paint, and printing industries. Chemical exposure has also been associated with bladder cancer in truck drivers, hairdressers, and machinists. In addition, areas of the world with high concentrations of arsenic in the groundwater have higher rates of bladder cancer. This includes Chile, Argentina, Taiwan, and some northeastern states of the United States.

Family History of Bladder Cancer

You may be twice as likely to develop bladder cancer if you have a close relative who has had the disease. A close relative includes a parent, sibling, or child. This possibility may be related to genetic factors that make it harder for the body to remove dangerous chemicals after exposure. In addition, an inherited disease linked to colorectal cancer called Lynch syndrome also increases the risk of bladder cancer.

Chronic Bladder Problems and Urinary Tract Infections

Long-term bladder irritation and inflammation, such as that caused by infections and bladder or kidney stones, make it more likely for someone to develop bladder cancer. People with spinal cord injuries are at risk of both chronic infections and kidney stones. A parasitic infection called schistosomiasis increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. This infection is rare in the United States but common in the Middle East.

Age

People with bladder cancer are most likely to develop the disease after age 70.

Gender

Men are more likely than women to develop bladder cancer. Overall, the chance that men will develop this cancer during their life is about one in 27. For women, the chance is about one in 89.

Prior Chemotherapy or Radiation

Certain chemotherapy drugs increase the long-term risk of developing bladder cancer. Cyclophosphamide is one of these medications. In addition, some studies have suggested that radiation treatment to the pelvis may increase the risk of developing bladder tumors.

Diabetes Medication

Pioglitazone (Actos®) is a drug taken by people with type 2 diabetes to lower blood sugar. The Food and Drug Administration has associated pioglitazone with an increased risk of bladder cancer.

Cystoscopy and Transurethral Resection

A cystoscopy is a procedure in which a small tube with a camera is inserted into the urethra (the duct through which urine leaves the body) and slowly moved into the bladder. This allows the doctor to examine the lining of the bladder and take a sample (biopsy). A cystoscopy and transurethral resection or biopsy — removal of the sample through the urethra — is typically done using anesthesia. People who have a cystoscopy can usually go home the same day.

Urine Cytology

A urine sample called urine cytology can be checked for cancer cells.

Imaging of the Urinary Tract

Various imaging tests can be used to examine the urinary tract. These may include:

- CT scans, which obtain cross-sectional pictures of the body and can help doctors

determine if the cancer cells are only in the bladder or if they have spread to other areas

- MRI, which can help doctors see if the cancer has invaded the muscle in the bladder wall and, if so, how deeply

- PET scans, which take images that help doctors tell apart active and dormant tissue to help determine whether it’s normal or cancerous

These imaging tests often involve contrast dye that is injected into your hand or arm. The dye flows into your bladder to identify areas that might be cancerous.

Bladder Cancer Cystoscopy

Doctors examine the inside of the bladder through a procedure called a cystoscopy. During a cystoscopy, a doctor inserts a thin lighted instrument called a cystoscope into the bladder through the urethra. A cystoscopy to examine the bladder can be performed with local anesthesia in an office. A cystoscopy with transurethral resection to get a sample (biopsy) or remove tumors is typically done with general anesthesia. People who have a cystoscopy can usually go home the same day.

Cystoscopy for Biopsy

Some people with bladder cancer may need to have a biopsy. This involves taking a small sample from the bladder and examining it for cancer cells. A pathologist looks at the sample under a microscope to make a diagnosis. Our pathologists are highly skilled at analyzing samples to accurately identify bladder cancer subtypes and determine the stage of bladder cancer.

Cystoscopy for Early-Stage Bladder Cancer

For early-stage bladder cancer, doctors may be able to remove the entire tumor using cystoscopy alone. This is especially likely for people with urothelial bladder cancer confined to the inner tissues of the bladder (stages 0 and I).

Doctors classify bladder cancer according to the type and stage, from the earliest to the most advanced. When our doctors know the stage of the cancer, we can prepare a treatment plan that’s customized specifically to each person’s needs.

The stages of bladder cancer are based on the location and size of the tumor and how far it may have spread.

The main stages of bladder cancer are:

Stage 0 Bladder Cancer

- Stage 0 describes non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. It is found only on the surface of the inner lining of the bladder. This stage is also known as in situ. Stage 0 bladder cancer is typically treated with transurethral resection (TUR), followed by either close follow-up without further treatment or intravesical therapy using bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy to try to keep the cancer from coming back.

Stage I Bladder Cancer

- Stage I describes superficial non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. It is present in the bladder’s inner lining but hasn’t invaded the muscle wall. We usually perform an initial TUR to determine the extent of the cancer as well as the grade. We typically do a second TUR to remove the rest of the tumor followed by intravesical therapy with either BCG or chemotherapy.

Stage II Bladder Cancer

- Stage II cancer has invaded the muscle of the bladder wall but is still confined to the bladder. Depending on the extent and grade of the cancer, we may recommend a partial or total (radical) cystectomy. Some people may need chemotherapy before surgery. We may be able to remove the tumor with TUR followed by radiation and chemotherapy.

Stage III Bladder Cancer

- Stage III describes a tumor that has spread through the bladder wall to surrounding tissue or organs and possibly to lymph nodes near the bladder. This is usually treated with a radical cystectomy combined with chemotherapy before the surgery and sometimes after as well.

Stage IV Bladder Cancer

- Stage IV cancer is the most advanced form of bladder cancer. It is called metastatic. This means the cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes or organs. Cancers that have spread beyond the bladder into the wall of the abdomen or pelvis are also considered Stage IV. Stage IV cancer is usually treated with chemotherapy and, more recently, with immunotherapy as well.

People with bladder cancer of all stages may be able to participate in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies that test new treatments to see how well they work.

What is metastatic bladder cancer?

Metastatic (stage IV) bladder cancer has spread beyond the bladder to the wall of the abdomen or pelvis. It may also have spread to lymph nodes and distant sites in the body. It is usually treated with chemotherapy and, more recently, immunotherapy.

Bladder Cancer Grades

In addition to the stages, bladder cancer can be divided into low-grade or high-grade tumors. The grade refers to how the cells look under a microscope.

Low Grade Bladder Cancer

- Low-grade bladder cancer cells are close in appearance to normal cells. They usually grow more slowly and are less likely to invade the muscle wall of the bladder compared with high-grade tumors.

High Grade Bladder Cancer

- High-grade bladder cancer cells appear abnormal, grow more quickly, and are likely to spread.

We may recommend surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of these to treat bladder cancer. Preserving or recreating your bladder is one of our key goals.

The overall treatment approach is guided by whether your bladder cancer has grown into the muscle or spread further. Each of these categories has its own treatment plan.

Before we recommend any treatment, you will meet with a surgeon. In most cases, you will also see a medical oncologist. This ensures that experts in both specialties thoroughly evaluate you to determine the best treatment plan for you.

Bladder Cancer Surgery

Surgery is usually the first treatment for bladder cancer that has not spread to other parts of the body. We offer many kinds of surgery for people with bladder cancer. This includes transurethral resection of the bladder tumor for early-stage disease. For more-advanced disease, we may perform a cystectomy. This is the removal of the bladder. If the bladder needs to be removed, we may be able to create a new bladder, called a neobladder, using intestinal tissue.

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Therapy for Bladder Cancer

If there is a high risk of the bladder cancer returning after surgery, we may recommend a type of immunotherapy called bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy. It is given once a week for six weeks. This therapy is designed to trigger an inflammatory response in the bladder that prevents the tumor from growing. We deliver BCG therapy directly to the bladder through a tube placed in the urethra.

Chemotherapy for Bladder Cancer

Chemotherapy is a drug or combination of drugs that kills cancer cells wherever they are in the body. After surgery for early-stage bladder cancer that has not grown into the muscle, we may give chemotherapy directly into the bladder through a tube placed in the urethra. For later-stage bladder cancer, we may give systemic chemotherapy. This form of chemotherapy is usually injected into a vein. The drugs circulate throughout the body and kill cancer cells wherever they are.

Radiation Therapy for Bladder Cancer

Radiation therapy may be given either before surgery to shrink the cancer or after surgery to destroy any cancer cells that are left. Our doctors may recommend radiation for people having surgery to preserve their bladder. We may also use radiation in place of surgery depending on the specifics of the cancer.

Immunotherapy for Bladder Cancer

Immunotherapy triggers the body’s immune system to fight cancer cells. We give immunotherapy systemically to treat cancer that has spread. has led the way in developing immunotherapy drugs. Our doctors continue to study and investigate them in clinical trials.

If bladder cancer has not spread to other parts of the body, our doctors will most likely recommend surgery. Our bladder surgeons are among the most highly experienced in the world in using all approaches. They work closely with pathologists, medical oncologists, and many other cancer experts.

We have the depth of knowledge to perform a procedure at the right time, in the right way, and in combination with the right additional therapies. To get you back to normal day-to-day activities as soon as possible, your bladder cancer surgeon will use surgical techniques that can limit your side effects and speed your recovery.

Transurethral Resection (TUR) and Bladder Preservation

Transurethral resection (TUR) is the most common type of surgery for bladder cancer. It is used to treat early-stage bladder cancer that has not grown into the muscle. The surgeon inserts a cystoscope through the urethra (the duct through which urine leaves the body) and into the bladder to remove any tumors. The tumors are then sent to a lab to be examined by a pathologist. The pathologist can help determine whether additional treatment may be needed. After the procedure, you can usually return home the same day or the next day.

TUR alone may be able to eliminate bladder cancer that has not grown into the muscle. However, we may recommend additional treatments to lower the risk of the cancer returning. These may include bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy or intravesical chemotherapy.

Cystectomy, Neobladder, and Urinary Diversion

A cystectomy is surgery to remove the bladder. This procedure is used to treat bladder cancer that has grown into the muscle. A partial cystectomy removes only a portion of the bladder. A radical cystectomy removes the entire bladder as well as nearby lymph nodes and organs that may contain cancer.

During a partial or radical cystectomy, the surgeon may be able to create a new bladder, called a neobladder. It is built from part of the small intestine. If a neobladder is not possible, the surgeon may divert urine through part of the small intestine to an opening on the outside of the abdomen. This is called a stoma.

Chemotherapy is a drug or a combination of drugs that kills cancer cells wherever they are in the body. You may receive chemotherapy before or after surgery to increase the chance for a cure. If you have bladder cancer that has spread, you may receive chemotherapy as the main treatment when surgery is not an option.

Medical oncologists specialize in chemotherapy for bladder cancer. We will carefully tailor your treatment to make sure that it’s as effective as possible while helping maintain your quality of life. Your doctor will consider your specific circumstances. We will recommend specific chemotherapy treatments that minimize your side effects.

Before beginning chemotherapy, you’ll undergo a comprehensive evaluation to see how well you may tolerate certain treatments. This includes a careful consideration of your age, general health condition, and kidney, heart, and liver function. We also take into account the characteristics of the tumor.

Our doctors will develop the best chemotherapy plan for you — one that treats the cancer safely while preserving your quality of life.

Here you will find more in-depth information about chemotherapy for bladder cancer.

Intravesical Chemotherapy for Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

Intravesical therapies deliver a drug directly into the bladder through a catheter placed in the urethra (the duct through which urine leaves the body) instead of by mouth or into a vein. The drug stays in the bladder for one to two hours. Then it is drained out through the catheter or in urine. For early-stage (non-muscle-invasive) bladder cancer, we may give intravesical chemotherapy after transurethral resection to reduce the chance that the cancer will return. We typically use the drug mitomycin (Mitosol®) for intravesical chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy before Surgery for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

For muscle-invasive bladder cancer, our doctors may recommend chemotherapy before surgery. This treatment approach is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Large clinical studies have shown that this method improves cure rates and long-term survival for people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. We typically use the drugs gemcitabine (Gemzar®) and cisplatin for neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy after Surgery for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

Some people may have surgery without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In this case, chemotherapy after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) can kill any remaining cancer cells and reduce the chances that these cancer cells will form new tumors. For adjuvant chemotherapy, we use the same drugs, gemcitabine and cisplatin, that are used for neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Radiation therapy uses precisely focused high-energy beams to kill cancer cells. A doctors deliver radiation therapy in a variety of forms. The form we recommend depends on the type of cancer, the location of the tumor, and whether it has spread.

As part of your treatment for bladder cancer, you may receive radiation therapy before, during, or after surgery. This can shrink the tumors or destroy any remaining cancer cells. For some people, we may use radiation, often combined with a low dose of chemotherapy, in place of surgery altogether.

Our radiation oncologists use advanced techniques to target areas at risk while reducing radiation exposure to normal tissue.

Intraoperative Radiation Therapy during Bladder Cancer Surgery

Intraoperative radiation therapy is a treatment given during bladder cancer surgery to reduce the risk of the cancer returning. This approach delivers powerful radiation through thin tubes called catheters that are placed directly on the tissue. This can kill cancer cells that may remain after the tumor is removed. It is most commonly recommended if the cancer has spread beyond the bladder.

Because this treatment occurs during the surgery and can be delivered to a precisely defined area, it is possible to use a higher-than-usual dose of radiation. Normal tissue, especially the bowel, can be temporarily moved away from the treatment area or covered with shielding devices while radiation is delivered.

Intraoperative radiation treatment usually takes just a few minutes during the surgical procedure. Once the radiation dose is delivered, all radiation-related materials are removed and the operation continues.

External-Beam Radiation Therapy for Bladder Cancer

External-beam radiation therapy is the most common form of radiation treatment. It is delivered by a machine from outside the body. The radiation is most often in the form of X-rays. Sometimes the charged particles called protons or other types of energy are used. Our doctors may recommend external-beam radiation therapy combined with low-dose chemotherapy as an alternative to a cystectomy (removal of the bladder). This means the tumor is destroyed, but it leaves the bladder intact.

Image-Guided Radiation Therapy for Bladder Cancer

To verify the location of the tumor and the position of the bladder before and during the delivery of radiation treatment, we use a form of external-beam radiation therapy called image-guided radiation therapy. One challenge of delivering radiation therapy for bladder cancer is that the bladder moves as it empties and fills with urine. To target tumors precisely over multiple radiation treatments, we implant gold markers to show the exact location of the tumor and track the motion of the bladder from day to day.

We also use CT scanners linked to the machines delivering the radiation. The scanners allow us to visualize the bladder as well as normal surrounding tissue, such as the bowel and rectum. By using these advanced techniques, we can achieve high cure rates and maximize the chances of preserving a healthy bladder.

Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy for Bladder Cancer

The precise imaging methods we use when planning treatment allow us to safely and effectively use intensity-modulated radiation therapy. This technique uses computer programs to calculate and deliver varying doses of radiation directly to the tumor from different angles. Our radiation oncologists, in close collaboration with the medical physics team, played a leading role in developing this type of radiation therapy.

Immunotherapy is a new form of cancer treatment that uses the immune system to attack cancer cells. A form of immunotherapy called bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy is typically given after surgery for bladder cancer that hasn’t grown into the muscle.

In recent years, a new class of immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors has emerged. If the bladder cancer has spread, doctors may suggest one of these drugs instead of chemotherapy. In people who respond to checkpoint inhibitors, the drugs can have a more lasting effect than chemotherapy, with fewer side effects.

Checkpoint Inhibitor Drugs for Bladder Cancer

Checkpoint inhibitor drugs release a natural brake on the immune system. This allows the immune cells called T cells to recognize and attack tumors. The drugs work by blocking the interaction of a molecule called PD-1 on the surface of immune cells with a molecule called PD-L1 on the surface of cancer cells.

Beginning in 2014, five checkpoint inhibitor drugs became available for the treatment of bladder cancer:

- atezolizumab (Tencentriq®)

- pembrolizumab (Keytruda®)

- nivolumab (Opdivo®)

- avelumab (Bavencio®)

- durvalumab (Imfinzi®)