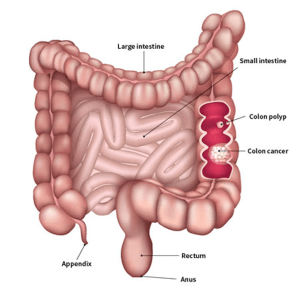

Colorectal cancer most often begins as a polyp, a noncancerous growth that may develop on the inner wall of the colon or rectum as people get older. If not treated or removed, a polyp can become a potentially life-threatening cancer. Finding and removing precancerous polyps can prevent colorectal cancer.

There are several forms of polyps. Adenomatous polyps, or adenomas, are growths that may become cancerous. They can be found with a colonoscopy Polyps are most easily found during a colonoscopy because they usually bulge into the colon, forming a mound on the wall of the colon that can be found by the doctor.

About 10% of colon polyps are flat and hard to find with a colonoscopy unless a dye is used to highlight them. These flat polyps have a high risk of becoming cancerous, regardless of their size.

Hyperplastic polyps may also develop in the colon and rectum. They are not considered precancerous.

It is important to remember that the symptoms and signs of colorectal cancer listed in this section are the same as those of extremely common conditions that are not cancer, such as hemorrhoids and IBS. When cancer is suspected, these symptoms usually have begun recently, are severe and long lasting, and change over time. By being alert to the symptoms or signs of colorectal cancer, it may be possible to detect the disease early, when it is most likely to be treated successfully. However, many people with colorectal cancer do not have any symptoms or signs until the disease is advanced, so people need to be screened regularly.

People with colorectal cancer may experience the following symptoms or signs. A symptom is something that only the person experiencing it can identify and describe, such as fatigue, nausea, or pain. A sign is something that other people can identify and measure, such as a fever, rash, or an elevated pulse. Together, signs and symptoms can help describe a medical problem. As mentioned above, it is also possible that the signs and symptoms described below may be caused by a medical condition that is not cancer, especially for the general symptoms of abdominal discomfort, bloating, and irregular bowel movements.

- A change in bowel habits

- Diarrhea, constipation, or feeling that the bowel does not empty completely

- Bright red or very dark blood in the stool

- Stools that look narrower or thinner than normal

- Discomfort in the abdomen, including frequent gas pains, bloating, fullness, and cramps

- Weight loss with no known explanation

- Constant tiredness or fatigue

- Unexplained iron-deficiency anemia, which is a low number of red blood cells

Talk with your doctor if any of these symptoms last for several weeks or become more severe. If you are concerned about any changes you experience, please talk with your doctor and ask to schedule a colonoscopy.

Because colorectal cancer can occur in people younger than the recommended screening age and in older people between screenings, anyone at any age who experiences these symptoms should visit a doctor to find out if they should have a colonoscopy.

Your doctor will ask how long and how often you’ve been experiencing the symptoms(s), in addition to other questions. This is to help figure out the cause of the problem, called a diagnosis.

If cancer is diagnosed, relieving symptoms remains an important part of cancer care and treatment. This may be called palliative care or supportive care. It is often started soon after diagnosis and continued throughout treatment. Be sure to talk with your health care team about the symptoms you experience, including any new symptoms or a change in symptoms

There are many types of colorectal cancer, the most common of which is adenocarcinoma. Other types include carcinoid tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, colorectal lymphoma.

Hereditary colorectal cancers, meaning that several generations of a family have had colorectal cancer, include hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

Here is an overview of some of the types of cancer in the colon and rectum:

- Adenocarcinoma

- Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST)

- Lymphoma

- Carcinoids

- Turcot Syndrome

- Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome (PJS)

- Familial Colorectal Cancer (FCC)

- Juvenile Polyposis Coli

Types of Colorectal Cancer

A risk factor is anything that raises your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed.

But having a risk factor, or even many, does not mean that you will get the disease. And some people who get the disease may not have any known risk factors.

Researchers have found several risk factors that might increase a person’s chance of developing colorectal polyps or colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer risk factors you can change

Many lifestyle-related factors have been linked to colorectal cancer. In fact, the links between diet, weight, and exercise and colorectal cancer risk are some of the strongest for any type of cancer.

Being overweight or obese

If you are overweight or obese (very overweight), your risk of developing and dying from colorectal cancer is higher. Being overweight raises the risk of colon and rectal cancer in people, but the link seems to be stronger in men. Getting to and staying at a healthy weight may help lower your risk.

Not being physically active

If you’re not physically active, you have a greater chance of developing colon cancer. Regular moderate to vigorous physical activity can help lower your risk.

Certain types of diets

A diet that’s high in red meats (such as beef, pork, lamb, or liver) and processed meats (like hot dogs and some luncheon meats) raises your colorectal cancer risk.

Cooking meats at very high temperatures (frying, broiling, or grilling) creates chemicals that might raise your cancer risk. It’s not clear how much this might increase your colorectal cancer risk.

Having a low blood level of vitamin D may also increase your risk.

Following a healthy eating pattern that includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and that limits or avoids red and processed meats and sugary drinks probably lowers risk.

Smoking

People who have smoked tobacco for a long time are more likely than people who don’t smoke to develop and die from colorectal cancer. Smoking is a well-known cause of lung cancer, but it’s linked to a lot of other cancers, too. If you smoke and want to know more about quitting, see our Guide to Quitting Smoking.

Alcohol use

Colorectal cancer has been linked to moderate to heavy alcohol use. Even light-to-moderate alcohol intake has been associated with some risk. It is best not to drink alcohol. If people do drink alcohol, they should have no more than 2 drinks a day for men and 1 drink a day for women. This could have many health benefits, including a lower risk of many kinds of cancer.

Colorectal cancer risk factors you cannot change

Being older

Your risk of colorectal cancer goes up as you age. Younger adults can get it, but it’s much more common after age 50. Colorectal cancer is rising among people who are younger than age 50 and the reason for this remains unclear.

Recommends external icon that adults age 45 to 75 be screened for colorectal cancer. The decision to be screened between ages 76 and 85 should be made on an individual basis. If you are older than 75, talk to your doctor about screening. People at an increased risk of getting colorectal cancer should talk to their doctor about when to begin screening, which test is right for them, and how often to get tested.

Several screening tests can be used to find polyps or colorectal cancer. The Task Force outlines the following colorectal cancer screening strategies. It is important to know that if your test result is positive or abnormal on some screening tests (stool tests, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and CT colonography), a colonoscopy test is needed to complete the screening process. Talk to your doctor about which test is right for you.

Stool Tests

- The guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) uses the chemical guaiac to detect blood in the stool. It is done once a year. For this test, you receive a test kit from your health care provider. At home, you use a stick or brush to obtain a small amount of stool. You return the test kit to the doctor or a lab, where the stool samples are checked for the presence of blood.

- The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) uses antibodies to detect blood in the stool. It is also done once a year in the same way as a gFOBT.

- The FIT-DNA test (also referred to as the stool DNA test) combines the FIT with a test that detects altered DNA in the stool. For this test, you collect an entire bowel movement and send it to a lab, where it is checked for altered DNA and for the presence of blood. It is done once every three years.

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

For this test, the doctor puts a short, thin, flexible, lighted tube into your rectum. The doctor checks for polyps or cancer inside the rectum and lower third of the colon.

How often: Every 5 years, or every 10 years with a FIT every year.

Colonoscopy

This is similar to flexible sigmoidoscopy, except the doctor uses a longer, thin, flexible, lighted tube to check for polyps or cancer inside the rectum and the entire colon. During the test, the doctor can find and remove most polyps and some cancers. Colonoscopy also is used as a follow-up test if anything unusual is found during one of the other screening tests.

How often: Every 10 years (for people who do not have an increased risk of colorectal cancer).

CT Colonography (Virtual Colonoscopy)

Computed tomography (CT) colonography, also called a virtual colonoscopy, uses X-rays and computers to produce images of the entire colon, which are displayed on a computer screen for the doctor to analyze.

How often: Every 5 years.

Staging is a way of describing where the cancer is located, if or where it has spread, and whether it is affecting other parts of the body.

Doctors use diagnostic tests to find out the cancer’s stage, so staging may not be complete until all of the tests are finished. Knowing the stage helps the doctor recommend what kind of treatment is best and can help predict a patient’s prognosis, which is the chance of recovery. There are different stage descriptions for different types of cancer.

TNM staging system

One tool that doctors use to describe the stage is the TNM system. Doctors use the results from diagnostic tests and scans to answer these questions:

- Tumor (T): Has the tumor grown into the wall of the colon or rectum? How many layers?

- Node (N): Has the tumor spread to the lymph nodes? If so, where and how many?

- Metastasis (M): Has the cancer spread to other parts of the body? If so, where and how much?

The results are combined to determine the stage of cancer for each person.

There are 5 stages: stage 0 (zero) and stages I through IV (1 through 4). The stage provides a common way of describing the cancer, so doctors can work together to plan the best treatments.

Here are more details on each part of the TNM system for colorectal cancer:

Tumor (T)

Using the TNM system, the “T” plus a letter or number (0 to 4) is used to describe how deeply the primary tumor has grown into the bowel lining. Stage may also be divided into smaller groups that help describe the tumor in even more detail. Specific tumor information is listed below.

TX: The primary tumor cannot be evaluated.

T0 (T plus zero): There is no evidence of cancer in the colon or rectum.

Tis: Refers to carcinoma in situ (also called cancer in situ). Cancer cells are found only in the epithelium or lamina propria, which are the top layers lining the inside of the colon or rectum.

T1: The tumor has grown into the submucosa, which is the layer of tissue underneath the mucosa or lining of the colon.

T2: The tumor has grown into the muscularis propria, a deeper, thick layer of muscle that contracts to force along the contents of the intestines.

T3: The tumor has grown through the muscularis propria and into the subserosa, which is a thin layer of connective tissue beneath the outer layer of some parts of the large intestine, or it has grown into tissues surrounding the colon or rectum.

T4a: The tumor has grown into the surface of the visceral peritoneum, which means it has grown through all layers of the colon.

T4b: The tumor has grown into or has attached to other organs or structures.

Node (N)

The “N” in the TNM system stands for lymph nodes. The lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped organs located throughout the body. Lymph nodes help the body fight infections as part of the immune system. Lymph nodes near the colon and rectum are called regional lymph nodes. All others are distant lymph nodes that are found in other parts of the body.

NX: The regional lymph nodes cannot be evaluated.

N0 (N plus zero): There is no spread to regional lymph nodes.

N1a: There are tumor cells found in 1 regional lymph node.

N1b: There are tumor cells found in 2 or 3 regional lymph nodes.

N1c: There are nodules made up of tumor cells found in the structures near the colon that do not appear to be lymph nodes.

N2a: There are tumor cells found in 4 to 6 regional lymph nodes.

N2b: There are tumor cells found in 7 or more regional lymph nodes.

Metastasis (M)

The “M” in the TNM system describes cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver or lungs. This is called metastasis.

M0 (M plus zero): The disease has not spread to a distant part of the body.

M1a: The cancer has spread to 1 other part of the body beyond the colon or rectum.

M1b: The cancer has spread to more than 1 part of the body other than the colon or rectum.

M1c: The cancer has spread to the peritoneal surface.

Grade (G)

Doctors also describe this type of cancer by its grade (G). The grade describes how much cancer cells look like healthy cells when viewed under a microscope.

The doctor compares the cancerous tissue with healthy tissue. Healthy tissue usually contains many different types of cells grouped together. If the cancer looks similar to healthy tissue and has different cell groupings, it is called “differentiated” or a “low-grade tumor.” If the cancerous tissue looks very different from healthy tissue, it is called “poorly differentiated” or a “high-grade tumor.” The cancer’s grade may help the doctor predict how quickly the cancer will spread. In general, the lower the tumor’s grade, the better the prognosis.

GX: The tumor grade cannot be identified.

G1: The cells are more like healthy cells, called well differentiated.

G2: The cells are somewhat like healthy cells, called moderately differentiated.

G3: The cells look less like healthy cells, called poorly differentiated.

G4: The cells barely look like healthy cells, called undifferentiated.

Which treatments are most likely to help you depends on your particular situation, including the location of your cancer, its stage and your other health concerns. Treatment for colon cancer usually involves surgery to remove the cancer. Other treatments, such as radiation therapy and chemotherapy, might also be recommended.

Surgery for early-stage colon cancer

If your colon cancer is very small, your doctor may recommend a minimally invasive approach to surgery, such as:

- Removing polyps during a colonoscopy (polypectomy). If your cancer is small, localized, completely contained within a polyp and in a very early stage, your doctor may be able to remove it completely during a colonoscopy.

- Endoscopic mucosal resection. Larger polyps might be removed during colonoscopy using special tools to remove the polyp and a small amount of the inner lining of the colon in a procedure called an endoscopic mucosal resection.

- Minimally invasive surgery (laparoscopic surgery). Polyps that can’t be removed during a colonoscopy may be removed using laparoscopic surgery. In this procedure, your surgeon performs the operation through several small incisions in your abdominal wall, inserting instruments with attached cameras that display your colon on a video monitor. The surgeon may also take samples from lymph nodes in the area where the cancer is located.

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. It is often called surgical resection. This is the most common treatment for colorectal cancer. Part of the healthy colon or rectum and nearby lymph nodes will also be removed.

While both general surgeons and specialists may perform colorectal surgery, many people talk with specialists who have additional training and experience in colorectal surgery. A surgical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer using surgery. A colorectal surgeon is a doctor who has received additional training to treat diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus. Colorectal surgeons used to be called proctologists.

In addition to surgical resection, surgical options for colorectal cancer include:

- Laparoscopic surgery. Some patients may be able to have laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. With this technique, several viewing scopes are passed into the abdomen while a patient is under anesthesia. Anesthesia is medicine that blocks the awareness of pain. The incisions are smaller and the recovery time is often shorter than with standard colon surgery. Laparoscopic surgery is as effective as conventional colon surgery in removing the cancer. Surgeons who perform laparoscopic surgery have been specially trained in that technique.

- Colostomy for rectal cancer. Less often, a person with rectal cancer may need to have a colostomy. This is a surgical opening, or stoma, through which the colon is connected to the abdominal surface to provide a pathway for waste to exit the body. This waste is collected in a pouch worn by the patient. Sometimes, the colostomy is only temporary to allow the rectum to heal, but it may be permanent. With modern surgical techniques and the use of radiation therapy and chemotherapy before surgery when needed, most people who receive treatment for rectal cancer do not need a permanent colostomy. Learn more about colostomies.

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or cryoablation. Some patients may have surgery on the liver or lungs to remove tumors that have spread to those organs. Optional treatments include using energy in the form of radiofrequency waves to heat the tumors, called RFA, or to freeze the tumor, called cryoablation. Not all liver or lung tumors can be treated with these approaches. RFA can be done through the skin or during surgery. While this can help avoid removing parts of the liver and lung tissue that might be removed in a regular surgery, there is also a chance that parts of tumor will be left behind.

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or a combination of different drugs given at the same time.

Chemotherapy may be given after surgery to eliminate any remaining cancer cells. For some people with rectal cancer, the doctor will give chemotherapy and radiation therapy before surgery to reduce the size of a rectal tumor and reduce the chance of the cancer returning.

Many drugs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat colorectal cancer in the United States. Your doctor may recommend 1 or more of them at different times during treatment. Sometimes these are combined with targeted therapy drugs (see “Targeted therapy” below).

- Capecitabine (Xeloda)

- Fluorouracil (5-FU)

- Irinotecan (Camptosar)

- Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

- Trifluridine/tipiracil (Lonsurf)

Some common treatment regimens using these drugs include:

- 5-FU alone

- 5-FU with leucovorin (folinic acid), a vitamin that improves the effectiveness of 5-FU

- Capecitabine, an oral form of 5-FU

- FOLFOX: 5-FU with leucovorin and oxaliplatin

- FOLFIRI: 5-FU with leucovorin and irinotecan

- Irinotecan alone

- XELIRI/CAPIRI: Capecitabine with irinotecan

- XELOX/CAPEOX: Capecitabine with oxaliplatin

- Any of the above with 1 of the following targeted therapies: cetuximab (Erbitux), bevacizumab (Avastin), or panitumumab (Vectibix). In addition, FOLFIRI may be combined with either of these targeted therapies (see below): ziv-aflibercept (Zaltrap) or ramucirumab (Cyramza).

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays to destroy cancer cells. It is commonly used for treating rectal cancer because this kind of tumor tends to recur near where it originally started. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time.

External-beam radiation therapy. External-beam radiation therapy uses a machine to deliver x-rays to where the cancer is located. Radiation treatment is usually given 5 days a week for several weeks. It may be given in the doctor’s office or at the hospital.

Stereotactic radiation therapy. Stereotactic radiation therapy is a type of external-beam radiation therapy that may be used if a tumor has spread to the liver or lungs. This type of radiation therapy delivers a large, precise radiation dose to a small area. This technique can help save parts of the liver and lung tissue that might otherwise have to be removed during surgery. However, not all cancers that have spread to the liver or lungs can be treated in this way.

Other types of radiation therapy. For some people, specialized radiation therapy techniques, such as intraoperative radiation therapy or brachytherapy, may help get rid of small areas of cancer that can not be removed with surgery.

- Intraoperative radiation therapy. Intraoperative radiation therapy uses a single, high dose of radiation therapy given during surgery.

- Brachytherapy. Brachytherapy is the use of radioactive “seeds” placed inside the body. In 1 type of brachytherapy with a product called SIR-Spheres, tiny amounts of a radioactive substance called yttrium-90 are injected into the liver to treat colorectal cancer that has spread to the liver when surgery is not an option. Limited information is available about how effective this approach is, but some studies suggest that it may help slow the growth of cancer cells.

Radiation therapy for rectal cancer. For rectal cancer, radiation therapy may be used before surgery, called neoadjuvant therapy, to shrink the tumor so that it is easier to remove. It may also be used after surgery to destroy any remaining cancer cells. Both approaches have worked to treat this disease. Chemotherapy is often given at the same time as radiation therapy, called chemoradiation therapy, to increase the effectiveness of the radiation therapy.

Chemoradiation therapy is often used in rectal cancer before surgery to avoid colostomy or reduce the chance that the cancer will recur. One study found that chemoradiation therapy before surgery worked better and caused fewer side effects than the same radiation therapy and chemotherapy given after surgery. The main benefits included a lower rate of the cancer coming back in the area where it started, fewer patients who needed permanent colostomies, and fewer problems with scarring of the bowel where the radiation therapy was given.

Radiation therapy is typically given in the United States for rectal cancer over 5.5 weeks before surgery. However, for certain patients (and in certain countries), a shorter course of 5 days of radiation therapy before surgery is appropriate and/or preferred.

A newer approach to rectal cancer is currently being used for certain people. It is called total neoadjuvant therapy (or TNT). With TNT, both chemotherapy and chemoradiation therapy are given for about 6 months before surgery. This approach is still being studied to determine which patients will benefit most.