Primary bone cancer, which begins in the bone itself (rather than spreading from another part of the body), is quite rare. It can grow in any of the bones in the body. Certain types emerge most often in the long bones of the arms and legs, while others occur most often in the pelvis, legs, ribs, and spine. It occurs most often in children and young adults, although it can affect people at any age. Bone cancer forms in the cells that make hard bone tissue.

Cancers that start in the bone marrow are not considered bone cancers. (These include leukemia, multiple myeloma, and lymphoma.) They do affect the bone, however, and may require treatment by bone specialists.

Benign (noncancerous) bone tumors are more common than malignant (cancerous) ones. Benign tumors do not spread and are rarely life threatening. But both types may grow and compress healthy bone tissue and absorb or replace it with abnormal tissue.

Metastatic bone cancer — cancer that starts somewhere else in the body and then spreads to the bone is much more common than primary bone cancer. Although any type of cancer can spread to the bone, the most common are breast, lung, kidney, thyroid, and prostate cancer. Bone metastases most often arise in the hip, femur (thigh bone), shoulder, and spine.

Symptoms of Bone Cancer

The most common symptom of bone cancer is pain, which is caused by either the spread of the tumor or the breaking of bone that is weakened by a tumor. You also may feel stiffness or tenderness in the bone. Sometimes there are other symptoms — such as fatigue, fever, swelling, and stumbling — but these can also be caused by other conditions. Only a doctor can tell for sure whether or not you have bone cancer.

There are several different types of bone cancer. Most primary bone cancers are in the category of tumors called sarcomas, a kind of cancer that can affect soft tissues such as muscles and nerves as well as bone. Sarcomas have a diverse range of features at the molecular and cellular level. Because of that, not all bone sarcomas respond to the same types of treatment.

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common type of primary bone cancer, making up about one third of cases. This cancer mainly affects children and young adults between the ages of 10 and 25. Osteosarcoma often starts at the ends of bones, where new tissue forms as children grow, especially in the knees.

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma is one of the most common types of primary bone cancer in people over age 50. It forms in cartilage, usually around the pelvis, knees, shoulders, or upper part of the thighs. This cancer makes up about a quarter of all primary bone cancer cases.

Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma usually occurs in the middle part of a bone, most often in the hips, ribs, upper arms, and thighs. Like osteosarcoma, this cancer affects mainly children and young adults between the ages of ten and 25. Ewing sarcoma is responsible for about 15 percent of primary bone cancer cases.

Rare Bone Cancers

The following bone cancers are rare and occur primarily in adults:

- Fibrosarcoma usually appears in the knees or hips. It can arise in older patients after radiation therapy for other cancers.

- Giant cell tumors, which usually begin in the knees, affect young adults most frequently and women more often than men.

- Adamantinoma usually occurs in the shin bone.

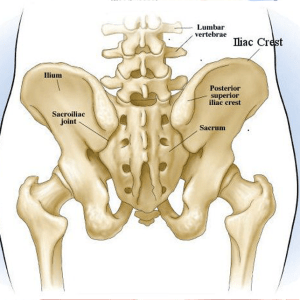

- Chordoma is found most often in the sacrum, which is the lower part of the spine, also known as the tailbone.

Bone Cancer Risk Factors

Age

Bone cancer occurs more frequently in children and young adults whose bones are still growing or have only recently stopped growing.

Previous Treatment for Cancer

Bone cancer is more common in people who have had radiation therapy or chemotherapy for other conditions, including other types of cancer.

Heredity

A small number of bone cancers are due to heredity. For example, children with hereditary retinoblastoma (an uncommon cancer of the eye) are at a higher risk of developing osteosarcoma.

Another hereditary condition that may increase bone cancer risk is Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a disorder caused by a mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor gene.

Other types of hereditary syndromes that have been linked to particular forms of bone cancer include Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, multiple exostoses syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis.

If it’s suspected that you have bone cancer, one of our doctors will first discuss your personal and family medical history with you. We will then perform a complete medical examination and do some tests.

Bone infections, noncancerous bone tumors, and other conditions may cause symptoms that could be confused with bone cancer. To accurately diagnose bone cancer, your doctor needs to know where it’s located in the body, how it appears on imaging studies, and the way the cells look under a microscope.

Metastatic bone cancer (cancer that formed in another part of the body and later spread to the bones) often has the same appearance and symptoms as primary bone cancer. A biopsy can determine where in the body the cancer began.

Laboratory Tests

One key test involves examining your blood to look for a specific enzyme that is often present at high levels when bone-forming cells are very active, called alkaline phosphatase. This kind of high activity occurs normally when a young child’s bones are growing or when a broken bone is mending. Otherwise, it could mean that a tumor is creating abnormal bone tissue. Since the enzyme may rise in response to other causes, high levels do not necessarily indicate that you definitely have bone cancer. But they do signal the need for further evaluation.

Biopsy

To make a definite diagnosis, we need to take a biopsy (a sample) of the suspicious bone tissue. If your tumor is small enough, we may remove the entire tumor, which is called an excisional biopsy.

In other cases, your doctor may make a small opening in your skin and remove just a small part of the tumor for analysis. This procedure is known as an open biopsy.

Or we may do a needle biopsy, in which we remove a sample of the tumor through your skin using a needle.

It is very important that an experienced and skilled surgeon perform the biopsy. An improperly performed biopsy may limit treatment options later on.

One of our pathologists will then examine the biopsy sample under a microscope. He or she will determine whether the tissue is cancerous and, if it is, identify the exact type of cancer. Determining which type of bone cancer you have is critical because not all types respond to the same kinds of treatment.

Diagnostic Imaging

We use imaging technology such as x-rays, CT scans, and MRI scans both after you are first diagnosed and throughout your treatment. Our goal is to monitor the tumor’s size and look for possible metastases (areas where the cancer has spread) or signs that the cancer has recurred (returned).

We usually begin with x-rays, which allow your doctor to see any unusual bone growths. This may be followed by a bone scan, to see if there are other abnormal areas in your bones. Before a bone scan, we inject a small amount of a slightly radioactive substance, known as a tracer, into a vein. After a few hours, the tracer collects where there is new bone growth. Often, we recommend a CT scan or MRI to show the exact size, shape, and extent of the suspected bone tumor and to determine if it has invaded surrounding tissue.

We also may perform a PET scan as part of your diagnosis. Unlike other imaging techniques that focus on a precise area, PET scans can show cancer growth throughout your whole body. PET and CT scans can be used in combination with each other to pinpoint the location of the cancer. Often, CT scans of the chest are used to see if the cancer has spread to your lungs.

Specialists from all areas of bone cancer care — including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and supportive care — work together to treat each patient. The team will design a treatment plan especially for you. Bringing together experts in different areas helps us choose the therapies that will most effectively treat your cancer and give you the best outcome possible. Preserving your quality of life is always one of our main goals.

Your treatment should be managed by a specialist centre with experience in treating bone cancer, where you’ll be cared for by a team of different healthcare professionals known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT).

Members of the MDT will include an orthopaedic surgeon (a surgeon who specialises in bone and joint surgery), a clinical oncologist (a specialist in the non-surgical treatment of cancer) and a specialist cancer nurse, among others.

Your MDT will recommend what they think is the best treatment for you, but the final decision will be yours.

Your recommended treatment plan may include a combination of:

- surgery to remove the section of cancerous bone – it’s often possible to reconstruct or replace the bone that’s been removed, although amputation is occasionally necessary

- chemotherapy – treatment with powerful cancer-killing medicine

- radiotherapy – where radiation is used to destroy cancerous cells

In some cases, a medicine called mifamurtide may be recommended as well.

Surgery is often the primary treatment for bone cancer. When operating to remove bone tumors, our surgeons remove some of the surrounding bone and muscle to be sure they are eliminating as much cancerous tissue as possible. If the cancer is in an arm or a leg, we try to preserve the limb and maintain its functionality. In most bone cancer surgeries, we are able to do so.

Sometimes we can replace bone that has been removed with either bone from another part of the body or an implant. We have developed replacements that are more durable and functional than those that were previously available.

We may use chemotherapy or radiation, or both, as part of your treatment, in combination with surgery. This is done either to shrink the tumor before surgery or to manage and control the tumor after surgery.

Preserving Limbs

While any diagnosis of cancer can be frightening, a bone cancer diagnosis often carries with it the additional worry about losing an arm or a leg. We try to preserve the limbs whenever we can reasonably do so. Our surgeons use a number of techniques for preserving limb function after bone cancer surgery. In some cases, the limb can be saved even when the bone needs to be removed. Our doctors can even recreate functioning joints, such as knees, so that your limbs will still flex naturally.

When amputation is necessary, our surgeons are skilled in performing the operation in a way that will allow you to have the best possible quality of life. There will always be a period of adjustment — both emotionally and physically — to the loss of a limb. But new surgical techniques and improved prostheses have made this adjustment easier. Usually you will be able to resume an active — even athletic — life after losing a limb or part of a limb to bone cancer.

Prostheses

Doctors have made many improvements in artificial limbs. We’ve developed replacements that are more durable and functional than standard replacements; participated in clinical trials to evaluate limb-replacement devices that may last longer than conventional prostheses; and led studies to create longer-lasting prostheses, such as the Compress implant, which secures a knee replacement to the thigh bone. We also use specially designed expandable prostheses in children that “grow” as a child grows.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery (the freezing and killing of cancer cells) is sometimes used in addition to surgery for some bone cancer patients. After removing the bone tumor, we use liquid nitrogen to freeze the tumor cavity to subzero temperatures. This kills microscopic tumor cells and decreases the chance that the tumor will recur (come back). The frozen bone is stabilized by filling the tumor cavity with bone graft, cement, or rods and screws to prevent fractures.

Surgeons were the first to use cryosurgery on bone tumors. They have perfected its use to reduce tumor recurrence, preserve the function of the limb and its joints, and decrease the need for amputation.

We often use chemotherapy in combination with surgery, radiation, or both to treat primary bone cancer. We typically give chemotherapy to kill any cancer cells that remain in the body after surgery to remove a tumor (called adjuvant chemotherapy). Sometimes we give chemotherapy before surgery (called neoadjuvant chemotherapy) to reduce the size of the tumor before our surgeons remove it.

Ewing Sarcoma

If you are diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma, we will treat you with chemotherapy to shrink the tumor and to prevent new tumors from forming.

Chemotherapy may cause damage to the bone marrow, which our doctors may need to treat as well.

If your cancer returns after initial treatment, we may use new drugs that have proven successful in treating Ewing sarcoma. We may also choose to perform additional surgery or radiation therapy. For this group of high-risk patients, we also offer a series of innovative, disease-specific clinical trials.

Chemotherapy for Ewing sarcoma may include:

- Vincristine

- Doxorubicin

- Cyclophosphamide

(This combination is known as VadriaC.)

This treatment may alternate with another regimen that includes:

- Ifosfamide

- Etoposide.

Your chemotherapy may also include:

- Irinotecan

- Temozolomide

Osteosarcoma

Treatment for osteosarcoma usually begins with chemotherapy, followed by surgery to remove the primary tumor and additional chemotherapy.

If your osteosarcoma has returned or spread, treatment options include chemotherapy drugs that may not have been previously used, as well as additional surgery and possibly radiation therapy. We offer a series of innovative, disease-specific clinical trials for this group of high-risk patients.

Common chemotherapy drugs for osteosarcoma are:

- Cisplatin

- Doxorubicin

- High-dose methotrexate

- Leucovorin

Chemotherapy may also include:

- Ifosfamide

- Etoposide

There have been many advances in radiation technology, and We sometimes give radiation therapy along with or instead of surgery to destroy tumors or shrink them. We may also use radiation therapy to kill any remaining cancer cells after surgery or to treat tumors that cannot be surgically removed, sometimes in combination with chemotherapy. If your cancer has spread and is pressing against or moving bone, we may also use radiation therapy to relieve your symptoms, including pain. Your doctor will explain which type of therapy would be best for you. Some of the common types of radiation are:

Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT)

The most common type of radiation therapy for bone cancer is intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). It uses sophisticated computer programs to calculate and deliver varying doses of radiation directly to the tumor from different angles. This allows your doctor to safely administer a higher dose and increases your chance for a cure.

Proton Therapy

For some patients, proton therapy may be best. This new method delivers radiation with less exposure to organs near the tumor. Proton treatment is especially popular for children because it can minimize the risk to healthy, growing tissues.

Stereotactic Radiosurgery

Stereotactic radiosurgery is a highly specialized and extremely precise technique. It involves delivering very high doses of radiation directly to tumors while minimizing the effects on surrounding healthy tissue. Because of the strength of the doses, it’s very likely to effectively control the tumor. And since the surrounding healthy tissue receives a much lower radiation dose, the risk of side effects is low. Our experienced team of radiation oncologists and medical physicists work together to perform stereotactic radiosurgery on primary bone cancer as well as cancer that has spread to the spine and other parts of the body.

Brachytherapy

Our doctors use brachytherapy to treat certain bone cancer cases. It is a form of internal radiation that delivers radiation therapy directly to the tumor itself. One common use is intraoperative radiation therapy, in which a large single dose of radiation is delivered directly to the tumor during surgery. Other types of brachytherapy involve temporary or permanent radioactive seeds that treat the inside of tumors.