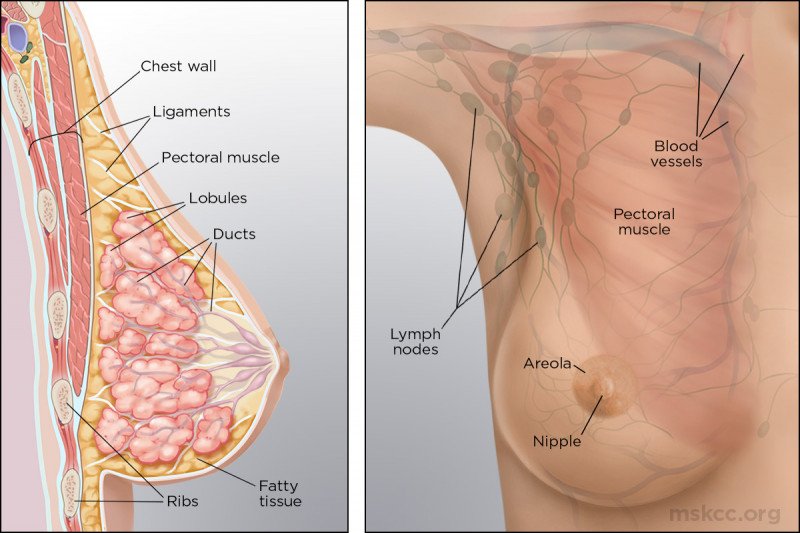

Breast cancer is a disease in which cells in the breast grow and multiply abnormally. This can happen if the genes in a cell that control cell growth no longer work properly. As a result, the cell divides uncontrollably and may form a tumor. You may be able to feel it as a lump under the skin, or you may not realize it’s there at all until it’s found on an imaging test, such as a mammogram(breast x-ray).

Keep in mind that most breast lumps are benign (not cancerous). That means they can’t spread and are not life-threatening. Malignant tumors are cancerous. If left untreated, cancer can invade surrounding tissue and spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body.

Many breast cancers are discovered through routine breast screening exams such as mammograms, even when a woman has no other signs of disease. However, on your own, you may notice symptoms that could be suspicious. See your doctor right away if you have any of these conditions:

- a lump or thickness in or near the breast or under the arm

- unexplained swelling or shrinkage of the breast, particularly on one side only

- dimpling or puckering of the breast

- nipple discharge (fluid) other than breast milk that occurs without squeezing the nipple

- breast skin changes, such as redness, flaking, thickening, or pitting that looks like the skin of an orange

- a nipple that becomes sunken (inverted), red, thick, or scaly

According to the Centers for Disease Control, most cancers are diagnosed in women over 55. As the percentage of older Americans continues to rise, we can expect an increase in the number of newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer.

Learn more about how different factors appear to slightly increase your risk for developing breast cancer.

- Age

- Personal history of breast cancer

- Family history of breast cancer

- BRCA and PALB2 gene mutations

- Early menstruation or late menopause

- Age at first pregnancy

- Benign breast disease

- Hormone replacement therapy

- Oral birth control

- Being overweight or obese

- Radiation exposure

Age

The risk of breast cancer increases with age.

- Women in their 30s have a one in 227 (0.44 percent) chance of developing breast cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute.

- In comparison, the risk for women in their 60s is one in 28 (3.6 percent).

- The lifetime breast cancer risk for women by the time they reach their 90s is about one in eight (12.4 percent).

Although the National Cancer Institute statistic of one in eight for women in their 90s is often cited, the actual risk of breast cancer for most women in any given year of their life is much lower than 12.4 percent.

Personal history of breast cancer

If you’ve had cancer in one breast, you’re more likely than the average woman to develop a new cancer in the other breast. In recent years the risk of a second breast cancer has decreased, however. This is because many drugs — especially the various anti-estrogen drugs — used for breast cancer treatment also reduce the risk of developing new breast cancers.

Family history of breast cancer

A significant number of women with breast cancer have some family history of the disease. But only 5 to 10 percent of all cases of breast cancer are due to heredity.

You may be two to three times more likely than the average woman to develop breast cancer if a first-degree relative (your mother, sister, or daughter) has had the disease. Many, but not all, cases of hereditary breast cancer are linked to mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Our understanding of their role and affect on risk continues to evolve.

BRCA and PALB2 gene mutations

Some cases of hereditary breast cancer are linked to mutations in the genes BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2. Mutations are changes in the molecular sequence of DNA. Having certain mutations in these genes raises the risk of breast cancer. A woman can inherit an abnormal gene from either her father or her mother.

The BRCA genes and the PALB2 gene normally function as caretakers. They help cells repair their DNA when it becomes damaged as a normal consequence of living. Women without a mutation have two normal copies of these genes, so they are at a lower risk of developing breast cancer than those with a mutation.

In most cases, a single normal gene is sufficient for good health. If that healthy gene is lost, only the mutated copy is left. This compromises a cell’s ability to repair its DNA. That’s when cancer can develop.

In addition to breast cancer, women with a BRCA mutation have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. Men with BRCA mutations may be at an increased risk of developing male breast cancer and prostate cancer. PALB2 mutations are also associated with pancreatic cancer.

You and your relatives might benefit from genetic counseling and testing if:

- several members of your family in multiple generations have had breast cancer or other forms of cancer — ovarian cancer or male breast cancer in particular

- your breast cancer occurred at a fairly young age (under age 50)

- your breast cancer occurred in both breasts

- your breast cancer is triple-negative, meaning it lacks the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 receptor

KIM’s Clinical Genetics Service offers hereditary cancer risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing by specially trained genetic counselors and doctors. If you are concerned about your personal or family history of cancer, our team of experts can help you make decisions about how to manage your risk.

Learn more about genetic testing and counseling at KIM’S

Early menstruation or late menopause

If you began having menstrual periods before age 12 or went through menopause after age 50, your risk of breast cancer is slightly higher than average. This may be because of the amount of the female hormone estrogen that your breasts have been exposed to throughout your lifetime. But the precise cause is not known.

Age at first pregnancy

If you had your first child after the age of 30 or have never had children, you’re at a slightly higher risk of breast cancer. This may be due to the protective changes in breast tissue that occur with full-term pregnancies.

Benign breast disease

Some noncancerous breast conditions may increase your risk of breast cancer. These include atypical hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ. Having had breast cysts, fibrocystic changes (which cause the breasts to feel lumpy), or small growths in the milk ducts called intraductal papillomas do not increase your risk of breast cancer.

Hormone replacement therapy

Using certain hormone replacement therapies after the beginning of menopause slightly raises your risk of breast cancer. This added risk disappears about three to five years after you stop taking the hormones. The risk is greatest for combination hormone replacement therapy. It uses both estrogen and progestin, as opposed to therapy using estrogen alone.

Oral birth control

Birth control pills raise your risk of breast cancer very slightly. The increased risk disappears about a decade after you stop taking them. Oral birth control is thought to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer.

Being overweight or obese

Excess weight increases your risk of breast cancer. It also increases the possibility that breast cancer will return after treatment, particularly after menopause. The likely reason is that being overweight increases the level of estrogen in the body.

Being overweight is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or higher. Obesity is defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher.

Radiation exposure

breast cancer is particularly strong for women who were exposed to radiation during the first two to three decades of their lives. This includes radiation to the chest for the treatment of cancers, such as lymphoma, as well as radiation to treat acne or an enlarged thymus gland. The amount of radiation from a mammogram, however, is very small and does not increase your risk by a significant degree.

Breast cancer types are determined by the way a sample of cells from the tumor, collected during a breast biopsy or breast cancer surgery, looks under a microscope. Breast cancers are also classified according to how sensitive they are to the hormones estrogen and progesterone, their levels of certain proteins that play a role in breast cancer growth (such as HER2), their genetic makeup, and other characteristics. This classification helps doctors predict how a cancer will respond to specific treatments, and it also allows them to personalize treatment.

Use this guide to learn about a variety of types of breast cancer and how they are classified.

- invasive breast cancer versus noninvasive breast cancer

- ductal carcinoma in situ

- invasive ductal carcinoma

- invasive lobular carcinoma

- lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia

- inflammatory breast cancer

- breast sarcoma

- metaplastic carcinoma

- estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer and progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer

- HER2-positive breast cancer

- What is triple-negative breast cancer

- breast papilloma, and is it cancer

If a physical exam, a mammogram, or other imaging tests show a suspicious change in one of your breasts, the next step is likely to be a biopsy. During a breast biopsy, a tissue sample is taken from your breast. It’s then examined under a microscope by a pathologist — a doctor who specializes in diagnosing disease — who can determine whether it contains cancerous cells.

Breast biopsies are performed in different ways based on your situation.

Fine-Needle Aspiration (FNA)

During an FNA procedure, a doctor inserts a very thin needle into the area of the breast with suspicious changes and removes a few cells. FNA is relatively quick, and any discomfort lasts only a few seconds. A pathologist examines the fluids or cells under a microscope to determine if they are benign (normal) or malignant (cancerous).

FNA is rarely used as the primary way to diagnose breast cancer because it doesn’t allow us to reliably tell the difference between in situ cancers and invasive ones. We often use FNA to evaluate whether breast cancer has spread to the axillary lymph nodes (located in the armpits) or other organs. In such cases, we can also test the expression of breast cancer tumor markers such as ER, PR, and HER2 in the tumor cells present in an FNA sample provided that enough cells are available.

Core Needle Biopsy

We use a core needle biopsy if we need a tissue sample that’s larger than what an FNA can get. We also use it if the tissue removed during an FNA doesn’t lead to a definitive diagnosis. Core needle biopsy requires the use of a local anesthetic to numb the area and a larger, hollow needle to remove a thin cylinder of tissue.

Core needle biopsy is the preferred method for sampling suspicious breast lesions. We routinely assess the expression of ER, PR, and HER2 in invasive carcinoma using core needle biopsy samples. The information obtained from a core needle biopsy informs the treatment plan your doctor recommends

Image-Guided Biopsy

Image-guided procedures use computer-imaging techniques to guide a needle into the breast to collect cells or tissue from a suspicious area. We use this method to diagnose suspicious areas that can be seen on a mammogram, ultrasound, or MRI but are too small to be felt by touch. Our breast imaging specialists have developed and shown the benefits of this approach. For most women, this type of breast biopsy can spare them a more uncomfortable and expensive surgical biopsy. It may also enable doctors to make a diagnosis more quickly so that women may start their treatment sooner.

A radiologist — a doctor whose specialty is using imaging tests to diagnose disease — performs this type of biopsy. He or she can pinpoint the exact location of the abnormal cells or tissue using x-ray, ultrasound, MRI, or other imaging techniques. Which technique is used depends on what the cells or tissue look like and what would create the best image of them.

Surgical Biopsy

A surgical biopsy is a brief procedure that takes place in an operating room but does not require you to stay in the hospital overnight. It does require you to be lightly sedated. The surgeon makes a small incision and removes either the entire mass of suspicious breast tissue or a representative sample, depending on its size and location.

We may recommend a surgical biopsy for two main reasons. The first is if other breast biopsy procedures don’t provide a clear diagnosis. The second is if the area containing possible cancer cells is too deep or too shallow for a fine needle aspiration or a core biopsy.

At some point, your doctor will tell you what stage your cancer is. Put simply, the stage describes how widespread or advanced the cancer is in the breast tissue and possibly other parts of your body. Determining the stage helps doctors explain the breadth of the cancer to you. It also helps them determine how to move forward with treatment, including surgery, if needed.

Breast cancer is also classified according to other characteristics. These include how sensitive it is to the hormones estrogen and progesterone as well as to the level of certain proteins that play a role in breast cancer growth, such as HER2. It is also classified by the cancer’s genetic makeup.

- stage 0 breast cancer

This is the very beginning of the scale. It describes noninvasive breast cancers or precancers. This includes the most common form of noninvasive cancer, called ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Within stage 0, there is no evidence that cancer cells or other abnormal cells have invaded neighboring normal tissue.

- stage I breast cancer

Stage I describes a very early stage of invasive cancer. At this point, tumor cells have spread to normal surrounding breast tissue but are still contained in a small area. Stage I is divided into two subcategories:

- In stage IA, a tumor measures up to 20 millimeters (about the size of a grape), and there’s no cancer in the lymph nodes.

- Stage IB can be described as either:

- a small tumor in the breast that is less than 20 millimeters plus small clusters of cancer cells in the lymph nodes; or

- no tumor in the breast plus small clusters of cancer cells in the lymph nodes.

- stage II breast cancer

Stage II describes cancer that is in a limited region of the breast but has grown larger. It reflects how many lymph nodes may contain cancer cells. This stage is divided into two subcategories.

Stage IIA is based on one of the following:

- Either there is no tumor in the breast or there is a breast tumor up to 20 millimeters (about the size of a grape), plus cancer has spread to the lymph nodes under the arm.

- A tumor of 20 to 50 millimeters is present in the breast, but cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage IIB is based on one of these criteria:

- A tumor of 20 to 50 millimeters is present in the breast, along with cancer that has spread to between one and three nearby lymph nodes.

- A tumor in the breast is larger than 50 millimeters, but cancer has not spread to any lymph nodes

- stage III breast cancer

In stage III breast cancer, the cancer has spread further into the breast or the tumor is a larger size than earlier stages. It is divided into three subcategories.

Stage IIIA is based on one of the following:

- With or without a tumor in the breast, cancer is found in four to nine nearby lymph nodes.

- A breast tumor is larger than 50 millimeters, and the cancer has spread to between one and three nearby lymph nodes.

In stage IIIB, a tumor has spread to the chest wall behind the breast. In addition, these factors contribute to assigning this stage:

- Cancer may also have spread to the skin, causing swelling or inflammation.

- It may have broken through the skin, causing an ulcerated area or wound.

- It may have spread to as many as nine underarm (axillary) lymph nodes or to nodes near the breastbone.

In stage IIIC, there may be a tumor of any size in the breast, or no tumor present at all. But either way, the cancer has spread to one of the following places:

- ten or more underarm (axillary) lymph nodes

- lymph nodes near the collarbone

- some underarm lymph nodes and lymph nodes near the breastbone

- the skin

- stage IV breast cancer

Stage IV is the most advanced stage of breast cancer. It has spread to nearby lymph nodes and to distant parts of the body beyond the breast. This means it possibly involves your organs — such as the lungs, liver, or brain — or your bones.

Breast cancer may be stage IV when it is first diagnosed, or it can be a recurrence of previous breast cancer that has spread.

Specialists from all areas of breast cancer care will design a treatment plan especially for you. Their areas of expertise include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, rehabilitation, and quality-of-life issues. Having all of them work together helps us ensure that we choose the best combination of therapies to treat your cancer and give you the best outcome possible.

- Breast Cancer Surgery

- Mastectomy

- Lumpectomy

- Lymph Node Biopsy

- Breast Prosthesis

- Systemic Therapy for Breast Cancer

- Radiation Therapy for Breast Cancer

- Breast Cancer Rehabilitation

- Breast Cancer Follow-up Care

If you have breast cancer, are considering a preventive mastectomy, or are helping a loved one learn about breast cancer treatment, you’ve come to the right place. We want to help you make these very personal choices to get the best outcome possible. This information is meant to guide you through your journey and prepare you for the decisions and choices you and your doctors will make together.

For most women, surgery will be part of treatment. Your options may include a lumpectomy (also called breast-conserving surgery), a mastectomy, or a mastectomy with breast reconstruction. The extent of the cancer, the size of your breasts, and your personal preferences will help determine which of these surgeries is the right choice for you.

Although breast cancer treatment usually starts with surgery, there are some situations in which your doctor may recommend chemotherapy first. For example, if you have a large tumor and small breasts, chemotherapy may shrink the tumor enough to make a lumpectomy possible. Having chemotherapy as the first treatment for breast cancer may destroy cancer in the lymph nodes, which may help some women avoid having their lymph nodes removed. For women with some types of advanced breast cancer such as inflammatory cancer, having chemotherapy as the first step in treatment is standard to be sure all the cancer cells can be removed surgically. In studies involving thousands of women, this has been shown to be just as safe as having surgery first.